Dead Babies and Climate Cowboys

“Do you ever wonder what happened in somebody’s life to make them such a miserable person?” sighed my friend, collapsing into a chair across from me at the coffee shop.

My friend, normally quite unflappable, had passed a pro-life protester and the ensuing exchange had left them feeling, for lack of a better word, flapped.

“I used to be that person waving signs with graphic images,” I smiled.

My friend raised their eyebrows.

In times like these, I find it easier to pull out a photo of my younger self on our family farm, wearing a head covering and floor-length calico dress. Looking at that image, I can feel my fifteen-year-old arms shaking as they held a pro-life sign high. The pain in my arms was nothing compared to the pain I was trying to save those babies from.

Fast forward several years. Those same arms held a sign advocating for reproductive rights in the Women’s March. They held a mic as I performed stand-up comedy and hosted a Femme Friday tea party to raise funds for women’s advocacy.

I’m still the same person who values human life. But different experiences and stories have changed my view on the best way to achieve that.

–

Lately, I’ve heard a lot of people express consternation that their loved ones are on “the other side.” In response, some skirt topics to avoid conflict, or slowly withdraw.

And in a political climate where name calling is commonplace, I tend to do the same.

“Gosh, I changed my entire world view after reading your facebook comment,” said no distant relative, ever.

But in a world where the resources we all share are at risk, perhaps a return to the more collaborative roots of our storytelling origins could help us find better solutions and bridge the gap between people with different views.

–

Storytelling is closely tied to the development of Mental Time Travel - our ability to predict what will happen next, learn from mistakes, and plan for the future. If you found a beautiful patch of berries, you could tell the rest of your group to help you gather them. If you developed a tool to capture an animal, you can tell the story of how it works. And if a mushroom kills your friend, you can tell the sad story and others can learn to avoid it.

I can’t help but wonder if this is why true crime podcasts are so popular. Maybe our deep fascination with the intricate details of the downfall of our fellow humans is part of our instinctual nature that has helped us survive. I like to imagine these mushroom gatherers as the original podcasters, relaying the story with flair, gasping as they mimicked convulsions and fell to the ground. The more memorable the retelling, the more likely others would avoid a similar fate.

This collaborative storytelling can help to combine knowledge for the betterment of the entire group. But there’s also another type of storytelling that helped us survive. Stories that establish an “in-group” and an “out-group” are super useful for group cohesion and rallying to protect your resources. In populist narratives, a “truth-teller” frames issues as a matter of a conflict between “us vs them.” A recent study looked at how both Donald Trump and Greta Thurnberg use populism as a form of storytelling. There’s nothing like a common enemy to bring people together.

If you were in the Battle of Helm's Deep being charged by an army of orcs and you said “hey guys, let’s put down our swords and talk about our feelings,” you probably wouldn’t be feeling anything much longer.

This type of “good guys vs bad guys” storytelling seems to be really popular these days. Don’t get me wrong - if our mushroom podcaster was tricking people into eating the wrong mushroom, you would want to call them out. Nobody wants a bad podcaster in their group.

But have the storytelling tools meant for our collective good been repurposed for individualistic interests? What if the real danger isn’t your neighbor with the annoying yard sign, but greater forces threatening the resources we all rely on?

In my years of helping people tell stories, I’ve interviewed many people who want the same thing, but have different perspectives on how to achieve it. And sometimes, both perspectives are necessary to create the whole picture.

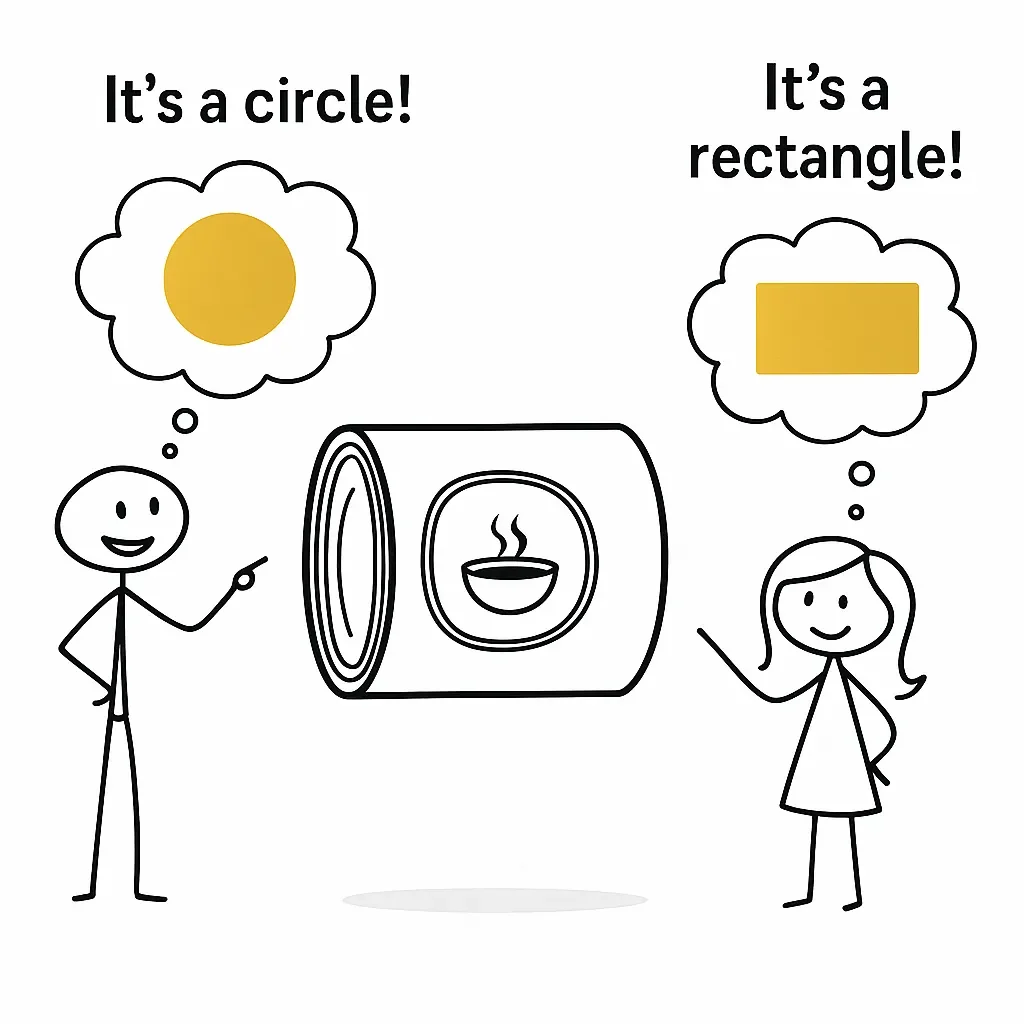

There’s a lore in Buddhism called the Elephant in the Dark. A group of blind men all touch different parts of an elephant and get into arguments about what an elephant is like. Another analogy is if we were all two-dimensional stick people, who perceived in two-dimensions, and encountered a three-dimensional soup can for the first time. The person looking at the top might say “It’s a circle!” and the person looking at the side might say “It’s a rectangle!”

two perspectives of the same thing, both with equal validity

Neither is wrong, but they’re not fully right either. They can go off and create the church of squares and the church of the circles, but in reality, both perspectives would create a more holistic understanding.

–

I met Lani Cran Petrie while co-directing the documentary Island Cowgirls. Lani is a Hawaiian cowgirl, or Paniolo, who manages Kapapala Ranch, 34,000 acres on the slopes of an active volcano on the Island of Hawai’i. Watching her gently move herds from one pasture to the next simply by calling them, it was clear she had a deep understanding of animals.

As I watched her strategic grazing methods, it was clear she also had a deep understanding of the land. For Lani, effective land management was all about understanding motivations. “What’s better,” she asked, “10,000 people with weed whackers, or 10,000 cows that are motivated because they are hungry?”

The importance of managing overgrowth was best exemplified in neighboring land, where ranchers had been removed years ago. But without funding or people to fully manage the land longterm, it had quickly become overgrown, and the moment a fire hit the overgrowth, it exploded. The 2018 Keahou Ranch Fire burned 3500 acres, but when it reached Lani’s property, however, there was no fire-load thanks to her hungry animals. Lani and her team held the fire at bay using water from their water reservoir.

It was Lani who first introduced me to the “three-legged stool” of sustainability. In this model, sustainability is the platform of a stool balanced on three legs - environmental, cultural, and economic. If any leg is missing, the solution can’t stand. Case in point, taking over land without an economically or socially sustainable plan to manage it long term.

a sustainable solution needs strong economic, social, and environmental legs

During Lani’s time tending the ranch, she had invested a million dollars to build a water reservoir that gathered rain and used all natural resources to water the entire ranch. But with Lani’s lease set to expire, the current terms of her lease under the Department of Land & Natural Resources (DLNR) were going to appraise her land with the new reservoir, forcing her to buy back her investments. These terms clearly disincentivized long-term investments in the land. I could get into the whole complicated story behind why the state is leasing back swaths of land to the same families who have managed it for generations before Hawaii even was a state, but the politics behind that are a whole other story.

In past visits to legislation, Lani had come up against conflicting opinions on what was best for her land. Our very first short film focused on her experiences and highlighted her desires for the land. It also highlighted her generational knowledge of this unique land and how to manage it. After watching the film, someone who had submitted testimony against a measure in the past called and said, “I think I might be on the wrong side of this, can I come visit?”

Over the following years, various leadership roles flew from Honolulu to see the ranch firsthand. In the years that followed, Kapapala Ranch received an Excellence in Ranch Management award. In 2023, the DLNR made the commitment to transfer her lease to the Department of Agriculture (DOA), a change in lease terms that would allow her to continue investing in long-term solutions. In the announcement, the DLNR Chair Dawn Chang said, “At the end of the day, we all want the same thing, what’s best for the land.”

Shortly after, Lani was invited to join a meeting with various environmental groups investing in caring for the health of the surrounding watershed. At her first meeting, the group was discussing a failed helicopter operation to remove invasive goats. Lani listened quietly, then offered, “If it were me, I’d just find a few females in heat, add a smelly billy goat, and lead the herd out. Once a few follow, the rest will come. I’ve moved hundreds if not thousands of cows out of places they weren’t supposed to be using this method.”

She smiled when she recalled their reaction: “Huh, it sure is nice having a rancher in the room.”

–

While Lani is still working with the state to finalize the promised transfer of her lease, she hasn’t stopped investing in the land. Most recently, she worked alongside soil scientists on an initiative to discover ways to better understand how to promote the health of the soil. While the funding for this USDA initiative was recently lost in the new administrative changes, Lani is resolved to continue the work on her own.

In my current documentary research, I’m exploring the ways land managers are continuing to work with science to better understand soil systems and restore them. While I’ve heard a lot about the important role of forests in our environment, my time with ranchers introduced me to a secret world of carbon sequestration happening in the underground forest of roots. I had no idea that cowboys could be part of a movement to address climate change. I had abandoned my agricultural upbringing alongside my head covering and calico dress. But circling back to my roots on my own terms has given me a new and nuanced appreciation for things like this.

—

Stories like Lani’s make me wonder how many other scenarios like this are out there, where two different groups might hold differing perspectives and information that could both be useful for creating a sustainable solution.

Different audiences require different types of storytelling. But bringing together people with different opinions requires a more collaborative form of storytelling.

In these cases, I like to start by sharing my experiences, struggles, desires, and obstacles I’ve overcome. In this way, I can share my experiences without making someone else feel inferior for having a different experience. And when you connect over shared desires, you can create an environment that invites curiosity and collaboration.

Because when we say “this is a circle and anyone who believes differently is an idiot,” we don’t leave room for other people’s valuable experiences. And in a world where we all share the same planet (at least for now), name calling could just kill us all.